Prepare.... but don't predict

<p> </p>

Article last updated 22 July 2025.

I’m regularly invited to join industry panels discussing various aspects of investing and I’ve been agog over the last few months at the number of times I’ve heard peers claim that they ‘know’ some of the things that Mr Trump was going to do once in office. While waiting in green rooms of the business TV channels, from time to time I’ve heard guests on the prior segment speak with similar assuredness. Implicitly or explicitly, all of these people were predicating investment cases on this ‘knowledge’.

For the most part, I very much doubt they do know exactly what Mr Trump is going to do. Nobody does, not for sure. A Washington-based political strategist we engage with tell us that members of Mr Trump’s own team – advisors and officials – don’t know for sure and that there are significant differences of opinion even among his closest allies. So I seriously doubt a Chief Investment Officer in London could be better informed.

We also don’t know in what order he’ll do things, and timing matters. Does the inflationary impact of tariffs or mass deportations come through before tax cuts or deregulation could lift growth? We don’t know. No one does.

The President’s own words throughout inauguration day should have served to remind people of his inscrutability. At first he presented a slow and measured approach to the introduction of tariffs, fuelling the bark-worse-than-bite school of optimism that characterises many equity investors. By the evening, that rhetoric had been replaced by musings about applying 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada within the fortnight.

For Mr Trump, tariffs are the Swiss army knife of policymaking. They can be used to shrink the trade deficit, devalue the currency, reindustrialize the heartland, raise revenues, stem migration, stop illegal immigrants crossing the Mexican border, as well as the trafficking of Chinese fentanyl. The logic of how they do all of that at the same time is pretty hard to follow. And so it’s unclear whether trade protection is his end goal, which could be quite negative for financial markets, or if his true aim is to extract concessions from trade partners on various matters, in which case the tariffs may be lifted quickly, and the market could enjoy a wonderful rally.

I thought it was interesting that President Trump spoke of ‘national security’ not as something inviolable but as something over which a deal could be brokered with China (this was in the context of the TikTok brouhaha). But investors must resist reading between the lines, especially when the orator isn’t exactly Oscar Wilde. In short, whether tariffs last for one month of twelve really matters. Investors today are none-the-wiser.

The bottom line is that investors are terrible at predicting politics and I believe industry commentators could use some humility here. At Rathbones, we prepare but we don’t predict. We closely analyse potential policy changes, understand what they could mean and stand ready to act if needs be. Meanwhile, we concentrate on building diversified portfolios invested in quality companies with a track record of resilience to a variety of economic and financial scenarios. More importantly, investors must not, through all the political fog, lose sight of the longer-term trends that really matter for markets.

Finding the right ballast

There are aspects of President Trump’s agenda that are very supportive of good returns on financial assets. These include tax cuts, some aspects of deregulation, cheap energy prices and a (possible) desire to rein in deficits which could lead to lower real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. Yet there are also aspects of the President’s agenda that could be rather negative: the inflationary impacts of aggressive tariffs and drastically shrinking immigration, the possibility of quite wayward spending that increases the deficit, and all at a time when the economy doesn’t have any spare capacity.

As I wrote above, we don’t believe investors are very good at predicting politics. Therefore, we should make sure that our portfolio diversification is well-conceived for a scenario in which equity markets are falling, when we need the diversification to function well well as a shock absorber.

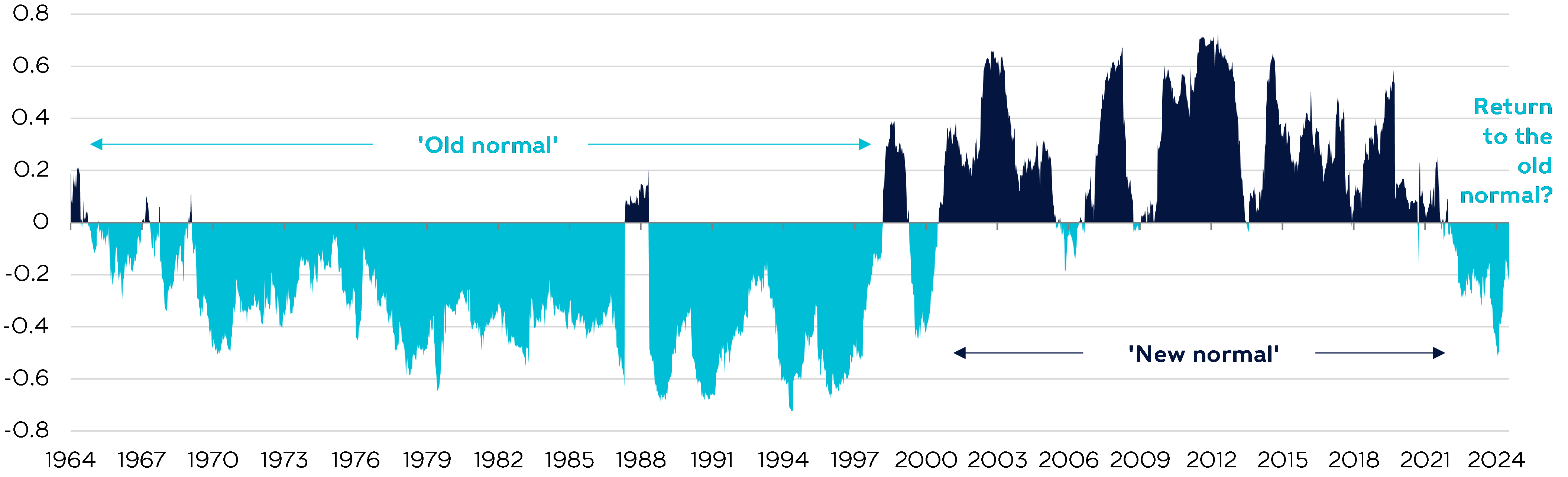

Fortunately, because an inflation spike is the channel through which ‘bad’ Trump policy could affect markets, the diversification challenge links to something we’ve already been thinking about for quite some time. It’s perhaps the most important question for long-term investors today: how do you make portfolios more resilient to a world where the correlation between equities – your portfolio’s return engine – and government bonds – your portfolio’s traditional ballast (your shock absorber) – may not be so reliably negative anymore? Because for most of the 19th and 20th centuries – for almost two hundred years – it wasn’t reliably negative. When equities fell, so did the value of bonds, which often happened when inflation spiked to uncomfortable levels (the chart below shows the correlation between equities and bond yields, which move inversely to bond prices, since the 1960s).

Correlation between equities and bond yields*

Source: LSEG, Rathbones; *1.0=perfectly correlated, with equities and bond yields moving in lock step

| Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. |

It may sound simple (it is), but shortening the average maturity of our bond holdings (and thereby making them less sensitive to interest rate volatility) is a very effective way of making our portfolios more resilient to a broad array of structural risks over the next 10 years (from changing Western policymaking, to less stable geopolitics, and the effects of climate change), without compromising our potential to make good returns in more benign conditions. You can read more about this in the ‘Keeping it short’ article in our latest Investment Insights publication.

Nothing ventured, nothing gained

Rounding off a big theme running through my Top 3 this quarter, President Trump’s policies could present significant upside as well as downside for investors. This uncertainty may seem unnerving. But if you take away only one lesson from 2024 into 2025 make it this one: don’t fear the unknown. Uncertainty does not always translate into market volatility.

In 2024, we had sticky core inflation (excluding volatile food and energy prices) on the final mile back to 2%, the general target for major central banks, alarmingly so in the first half of the year. We’ve had central bank policy pivots and a constant gyration of the number of rate cuts expected. We’ve had geopolitical tensions – including Israel and Iran launching missiles at each other and the Israel-Hamas war in Palestine spilling over into a proxy war in Lebanon – events that were on every investor’s list of red flags. We’ve had both France and Germany left effectively rudderless after ruling parties lost their mandate, with the former struggling with something of a fiscal crisis. And then we’ve had the contentious US election. Yet, despite all of that uncertainty, equity market volatility has been completely unremarkable.

Looking at the volatility of equities within each calendar year back to 1980, which measures how much and how fast prices move over the period, it is usually about 15.5%. In 2024 it was c.13%, notably below average. It’s easy to fear the unknown. There are a lot of unknowns today, but there are always a lot of unknowns. Various studies by psychologists and behavioural economists since the 1970s have shown that we are biased to perceiving the present as less certain than the past. It usually isn’t. Moreover, uncertainty does not always translate into market volatility as 2024 showed. Uncertainty can also mean upside. If you are willing and able to put capital at risk, fear of the unknown should not put you off investing your money.

The information in this article reflects our general views and should not be taken as financial advice or a recommendation.