For that reason, we’ve enhanced the way we account for climate change and climate policy in our ten-year assumptions for the global economy and markets, which in turn inform the way we construct portfolios. Climate discussions are sometimes emotive and politicised. But we’ve adopted a pragmatic and evidence-led approach.

How climate change is affecting the global economy

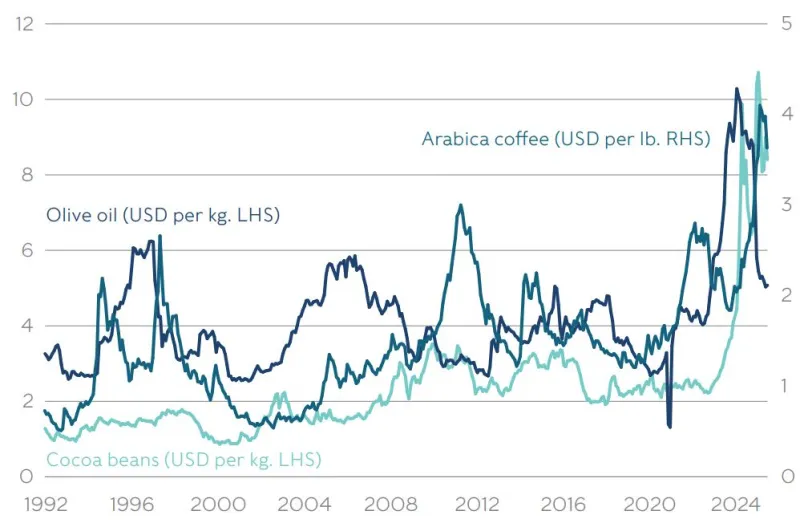

The recent historic spikes in the global prices of several agricultural commodities (figure 1) show how climate change is already having an impact. More frequent extreme weather events are contributing to higher and more volatile food inflation.

In southern Europe, drought and heatwaves hurt olive oil production in 2022, exacerbating supply shortages for other cooking oils caused by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and driving prices higher. Elsewhere, heatwaves and extreme precipitation have hurt cocoa harvests in West Africa. This played a role in the enormous run-up in the global price of cocoa beans. And droughts in Brazil and extreme weather in Vietnam have also helped push coffee prices to record highs.

Meanwhile, in the US, the impacts of intense Atlantic hurricanes have shown up in the economic data. On the other side of the continent, the frequency of wildfires causing major economic losses has risen. In both cases, there’s evidence that climate change has contributed.

The evidence doesn’t just come from single high-profile events. There are more subtle changes. In the UK, for example, the Office for National Statistics estimates that more frequent heatwaves are increasingly weighing on the economy, reducing GDP by 0.2% in 2020.

It isn’t just the physical effects of climate change that are visible. Policies to mitigate it are having an impact too. Rising prices in emissions trading schemes, through which companies buy and sell the right to emit carbon, could lead to higher inflation and slower economic growth in the short term. Meanwhile, in the US, President Biden’s roughly $1trn support for clean energy projects almost certainly had an impact on economic growth and inflation too.

The Trump administration plans to unwind some of that support, but climate spending continues elsewhere. For example, Germany’s historic change to its spending rules, approved by its parliament earlier in 2025, includes €100bn for climate-related investments.

Figure 1: Crop prices soar

The price of several agricultural commodities has surged recently

![A chat shows soaring prices of olive oil and arabica coffee into 2025]()

Source: International Monetary Fund; as at 18 June 2025.

How we’re factoring climate into our forecasts

Forecasting the effects of climate change comes with considerable uncertainty and there’s no perfect solution. We’re realistic about the limitations of even the best-informed efforts. But given the difference it makes to the global economy, it’s important we factor it into our long-run economic projections. To ignore climate change would be to assume it will have no impact. These economic projections inform our assessment of long-run asset returns — we’re happy to share information about our full methodology with clients on request.

Our new approach is to leverage modelling from a global network of experts from central banks and supervisory institutions known as the Network for Greening the Financial System, or NGFS. In addition to its huge collective experience in the field, the NGFS offers a broad range of scenarios and models, allowing us to form our own view on the future path of climate policy and reduce the risk that comes from relying on any single approach.

As with any forecasting, the NGFS’s modelling is imperfect and involves simplifications. But we think it offers the best available synthesis of academic rigour and practical usability, with conclusions that are neither extremely optimistic nor extremely pessimistic, compared with broader scientific opinion.

Three scenarios for climate policy — which is the most likely?

We’ve considered three NGFS scenarios in our latest round of forecasts:

- The first assumes merely that currently implemented climate policy remains in place, with no further action to reduce emissions and limit temperature rises — even if action is already pledged for the future.

- The second assumes that currently implemented climate policy is in place until the early 2030s, after which policies are strengthened.

- The third scenario assumes more stringent climate policies are implemented almost immediately, so that global net CO2 emissions reach zero around 2050. Net zero occurs when the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere is balanced by absorbing or avoiding an equivalent amount.

We currently give the first scenario the highest probability, followed by the second, with only a minimal chance of the third. This primarily reflects the reality that many countries are behind schedule on existing emission-reduction commitments. It also reflects recent political developments, including President Trump’s election and political events in Europe, such as a watering down of the new Labour government’s climate plans in the UK. This suggests that even if climate policies are strengthened, this is very unlikely during current electoral cycles.

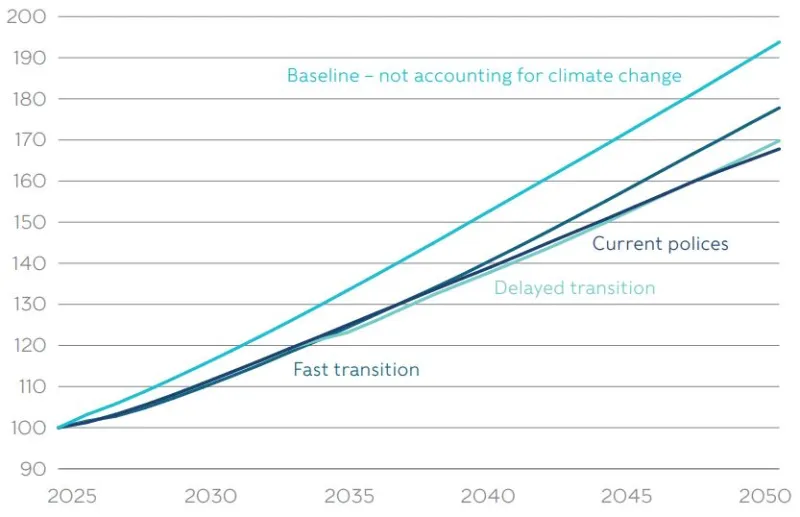

Slower economic growth, higher inflation

All three scenarios result in slower global GDP growth compared with a baseline forecast that takes no account of climate change (figure 2). They also predict higher inflation. At a more granular level, hotter, less developed, and more energy-intensive economies tend to see more adverse impacts. But while the reduction in GDP growth is significant, it’s only one consideration when updating our long-term forecasts, and often doesn’t have the largest impact over our ten-year horizon. In the US, for example, revised population projections and updated macroeconomic data this year more than offset the expected drag on economic growth from climate change and climate policy.

Perhaps most importantly, our conclusions support the view of the world we set out last year in our report on Investing for the Next Decade: slightly slower economic growth, higher and more volatile inflation, and by extension, higher and more volatile interest rates. This view has driven some of the changes we’ve been making to portfolios over the past year or so. One change has been to reduce the average years to maturity of bonds in portfolios. This is because bonds that mature further into the future are more sensitive to shifts in inflation and interest rates, so we think they could be more volatile than in recent decades. It’s also because history teaches us that long-dated bonds have been less reliable as an offset to stocks when inflation is higher.

Another step we’ve taken for some portfolios is to diversify returns by allocating to specialist strategies that aim to latch on to emerging price trends, including those driven by climate, across a wide range of global markets. In fact, some of the same commodity price spikes we’ve mentioned have been contributors to these strategies’ returns over the past few years.

Finally, we continue to take account of climate change through our analysis of specific sectors of the stock market. For example, we try and capture the risk that certain assets, such as oil and gas fields, are prematurely written down due to climate change.

Figure 2: A drag on global growth

Global GDP growth will be slowed by climate change, but it will continue.

![A chart shows how global growth will be slowed by climate change, but continue]()

Source: NGFS, Rathbones Asset Allocation Research; as at 18 June 2025; global GDP rebased to 100 in 2025.