How China’s generational shift is impacting its economy

<p>A recovery is expected for China’s economy this year, now that its zero-COVID restrictions have been scrapped and government policy has become more supportive. However, its longer-term challenges, such as a shrinking workforce and inefficient allocation of resources, remain. As a result, an initial cyclical rebound is likely to give way to structurally slower growth over the long term.</p>

<p>So, what could this mean for your clients’ investment portfolios?</p>

<p><strong>Swimming against the demographic tide</strong></p>

Article last updated 22 July 2025.

A recovery is expected for China’s economy this year, now that its zero-COVID restrictions have been scrapped and government policy has become more supportive. However, its longer-term challenges, such as a shrinking workforce and inefficient allocation of resources, remain. As a result, an initial cyclical rebound is likely to give way to structurally slower growth over the long term.

So, what could this mean for your clients’ investment portfolios?

Swimming against the demographic tide

One of the biggest challenges to China’s continued growth is that its working-age population has peaked and is expected to decline over the next decade, despite changes to the one-child policy. This is in sharp contrast to the US, where the population is expected to rise at a slow, but steady, rate. Indeed, it is expected that towards the end of the decade, China’s population will be contracting faster than Europe’s.

On top of this, strategies to offset the falling working-age population – in particular, by increasing labour-force participation by women – are not expected to have the same impact as they have had in other countries, such as Japan in the 1990s. This is due to female participation in the labour force already being quite high in China and comparable to other advanced economies.

Key capital growth sources slowing down

China’s growth model has long been enormously dependent on investment. During the 2000s and 2010s the country grew its capital stock at a breakneck pace, with few parallels in economic history. Yet there are clear reasons to doubt this will continue.

Housebuilding was a key contributor, partly reflecting fundamental demand from a growing population and rapid urbanisation. This demand is now clearly slowing. There may also be an overhang of vacant properties due to overbuilding in the 2010s, when speculation in the property market arguably led to excess construction.

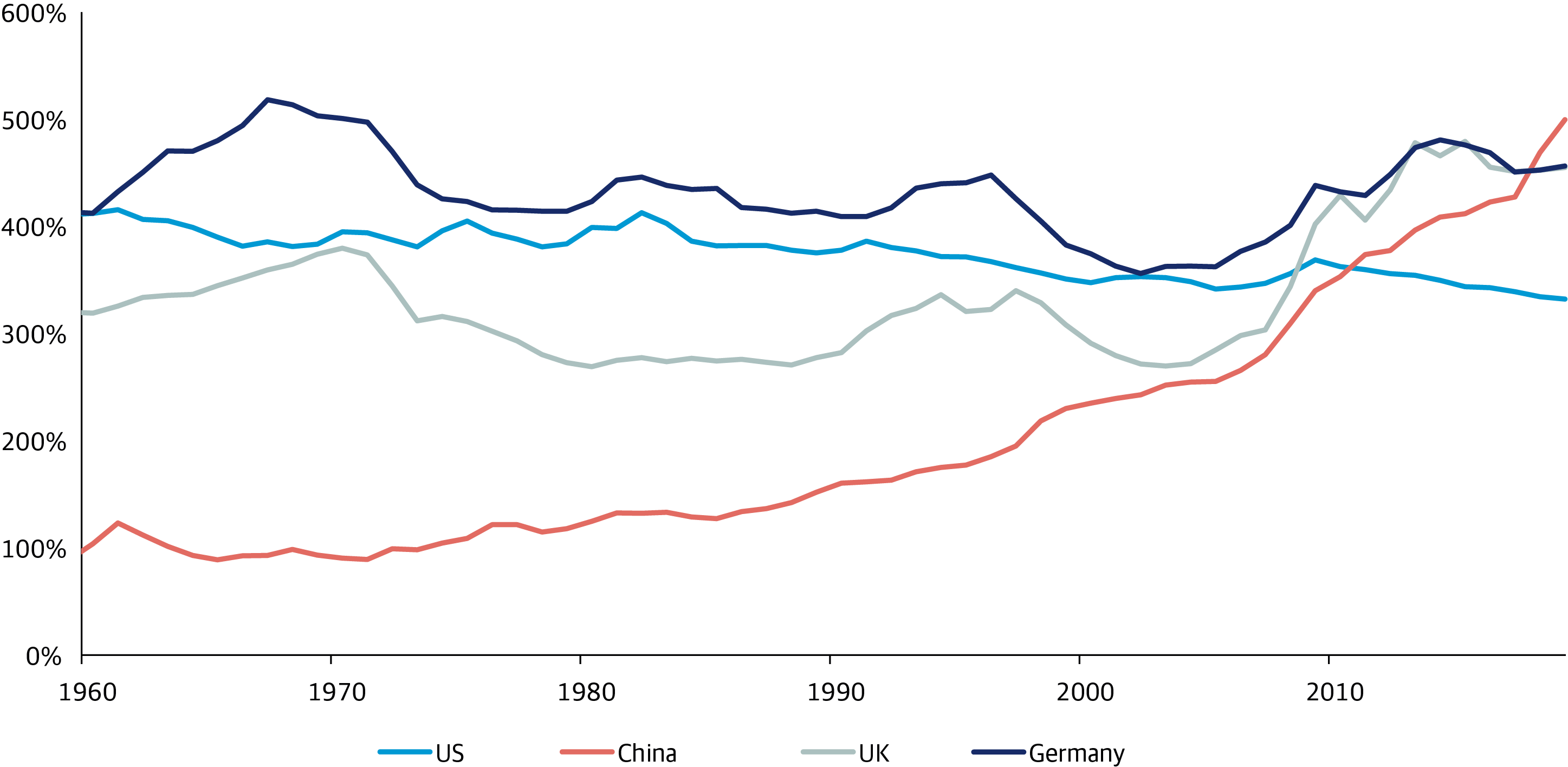

Another key element of China’s capital formation has historically been infrastructure building on a massive scale – but this is another area where growth is likely to be slower in future. While many other large economies have chronically underinvested in infrastructure over the past couple of decades, China has gone in the opposite direction. For example, it already has many more miles of high-speed rail than the rest of the world combined. Its capital stock is now as high relative to its GDP as in advanced economies (figure 1 below) – it doesn’t need to keep adding to it at a much faster rate.

State control threatening productivity

China has grown from a low-income country to an upper middle-income one since 2000. History shows that the next step, breaking out of the middle-income bracket to become a rich country on a per-capita basis (as Singapore, South Korea and Japan have done, for example) is hard.

If China is to move clearly into the ranks of rich countries, it will need to deliver consistent productivity growth. One factor which may stand in the way is the state’s role in the economy. The broad political trend towards greater state control in the economy – for example, the government’s regulatory role in the tech sector – is likely to make this harder in our view.

Geopolitics overshadow economics

Finally, regardless of China’s long-run economic prospects, growing legal and practical hurdles may make buying Chinese equities increasingly unappealing for foreign investors. The risks seem skewed towards more trade and investment restrictions, perhaps causing foreign ownership of Chinese equities to fall outright eventually.

Talk of a reset in US-China relations late last year amounted to nothing, with China’s President Xi Jinping now railing against US “containment, encirclement and suppression” of China. Taking a tough stance on China is one of the few issues that unites Democrats and Republicans in Washington. And China’s long-term aim of reunification with Taiwan is an obvious potential flashpoint.

What this means for your clients

While a cyclical rebound in China this year is likely, with many challenges to its long term growth still in play, and with the investment environment becoming harder to navigate, clients with an interest in long-term investment in China should be cautious.

Yes, China is likely to get a short-term boost to growth from its ‘great reopening’. But with the persistent headwinds still blowing against the three pillars of economic growth – labour, capital and productivity – coupled with the gusts from rising geopolitical tensions, it looks like investors can expect a lower speed limit on growth in China over the long term.

Our recently published China report offers more detail about our views of the country’s economy and long-term growth prospects. Read the full report here.