Breakthroughs in AI are exciting for investors, but we also see irrational exuberance.

Artificial intelligence and the search for company profits

Article last updated 12 December 2023.

The launch of ChatGPT has triggered a new artificial intelligence (AI) gold rush among investors. This search for riches has driven strong gains this year across the technology sector — from chip makers (the picks and shovels of this new gold rush) to large cloud-computing service providers, software vendors and IT consultants. But it’s far from clear how it will all pan out.

Machine learning is not a new phenomenon. At its heart, AI is applying statistical analysis to large data sets. For instance, Uber has been deploying this technology to match drivers and riders since 2015. Amazon uses it for product recommendations, Netflix to make us binge watch its programmes and PayPal for fraud detection. What’s new about this craze is that it’s generative AI. What makes this subset of machine learning different is that, instead of just trying to spot patterns in data, these algorithms appear to generate original content. This is what has captured the public and investors’ imaginations.

“I FEAR NONE OF THE EXISTING MACHINES; WHAT I FEAR IS THE EXTRAORDINARY RAPIDITY WITH WHICH THEY ARE BECOMING SOMETHING VERY DIFFERENT TO WHAT THEY ARE AT PRESENT.”

EREWHON BY SAMUEL BUTLER

Purple cats on the moon

Take pictures of cats, for example. Normal machine learning will be able to identify a cat after scanning millions of cat images. Not so long ago that seemed like a massive technological breakthrough. But it now seems rather quaint when compared with generative AI programmes like DALL-E 2, which can create entirely new images, such as a purple cat on the moon. The humanness of how the computer seems to interact with the data has led to ChatGPT’s release being described as an iPhone moment. Some commentators have gone as far as to say it will be as transformational as the Internet in the 2000s.

When we think about which companies will earn the fattest profits from generative AI, and whose lunch it might eat, it is useful to take a step back and look at the whole supply chain. When you look at the basic building blocks of these generative AI models, this machine learning is typically ‘trained’ on graphics processing (GPU) chips. These are almost all designed by Nvidia — 90% of all generative AI models are trained on its chips. They are mostly manufactured in Taiwan by TSMC, using equipment provided by ASML, a Dutch company. Most of these chips will be bought by Amazon, Meta, Microsoft and Alphabet and put into their data centres. Those four alone account for roughly half of Nvidia’s data-centre chip demand. These large cloud services providers (Microsoft’s Azure, Amazon’s AWS and Alphabet’s Google Cloud Platform) will then rent out that AI computing capacity to software developers and businesses to train and run their own AI programmes and models.

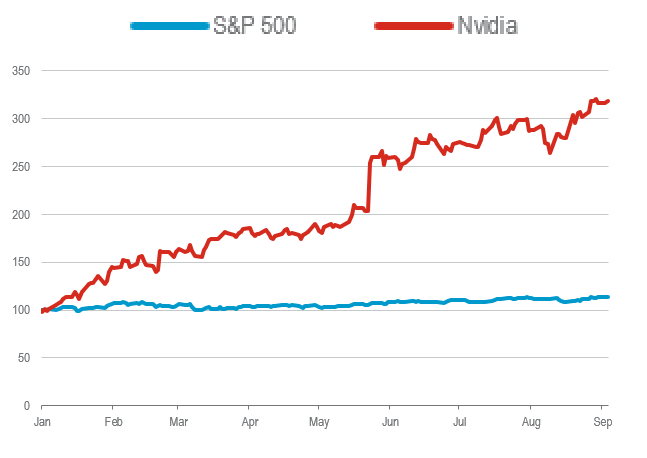

Figure 1: Chips with everything

Nvidia’s share price has surged this year as companies everywhere look for ways to adopt new artificial intelligence technologies — and need the company’s processing chips:

Rebased to 100 at beginning of 2023.

Source: Refinitiv, Rathbones.

Linguistic versions of generative AI, called large language models (LLMs) are available off the shelf from OpenAI (minority Microsoft owned) and Google. There are also open-source versions (where the software code is made freely available and can be redistributed and modified). Which one you use will depend on your IT resource. Interestingly, Uber has said it would prefer to use the free open-source option, and that LLMs are currently too expensive to deploy at the scale needed.

The value in the industry right now is almost entirely accruing to Nvidia, which is the ultimate provider of picks and shovels for this new AI goldrush. This became apparent when the company reported its blowout second-quarter results. Revenue doubled compared with the same period last year, on soaring demand for the GPU chips needed for generative AI training.

Monopolies in the cloud

As its rocketing share price indicates, Nvidia is raking in cash from selling chips to power generative AI (figure 1). The question is whether the firm can maintain this monopoly position given a huge economic incentive for the cloud service providers (their major customers) either to develop an in-house solution or to cultivate an alternative supplier.

There is a basic distinction in AI between training (teaching the AI to build a model) and inference (using that model in the wild). Training as mentioned is largely done on Nvidia chips, but inference can be done on multi-chip solutions including custom silicon designed in-house. The market for inference chips is thought to be significantly greater than training, which may limit Nvidia’s growth. When it comes to the rest of the tech sector — at all the layers further up the chain including the cloud services providers and the software applications — it’s not clear yet how generative AI will generate profits.

So far, the demonstrations of what this technology is capable of have been fairly trivial. So we’ve seen people use ChatGPT to write poems in cod Shakespearean dialect or DALL-E 2 to make funny images. Perhaps even here one could see a commercial application if it eliminates the need to hire copywriters (see jasper.ai) or graphic designers.

More pragmatic applications are likely to emerge. For example, Microsoft is embedding ChatGPT LLMs into its suite of Office applications for summarising calls or generating PowerPoint presentations. Intuit is using LLMs to help solve complex tax queries. Wendy’s to handle drive-through fast food orders and Uber in its call centres. Match Group to help daters initiate conversations with potential dates. Ironclad to rapidly draft and amend legal contracts. We can expect these language versions of generative AI to permeate the user interface of most applications.

Generating better earnings

The crucial point is that it is one thing to deploy generative AI and another to make money from it. It could turn out that generative AI is a feature that businesses need to incorporate in order to avoid obsolescence rather than to make bigger profits. For instance, Adobe has launched Firefly to generate art through natural language processing. If it hadn’t done this, a start-up could have offered this service and disrupted its business. Instead of generative AI boosting the earnings outlook for any company right now, it might become a cost of staying in business. Yet Adobe may yet find ways to commercialise this product and it will help tie users into its ecosystem of products.

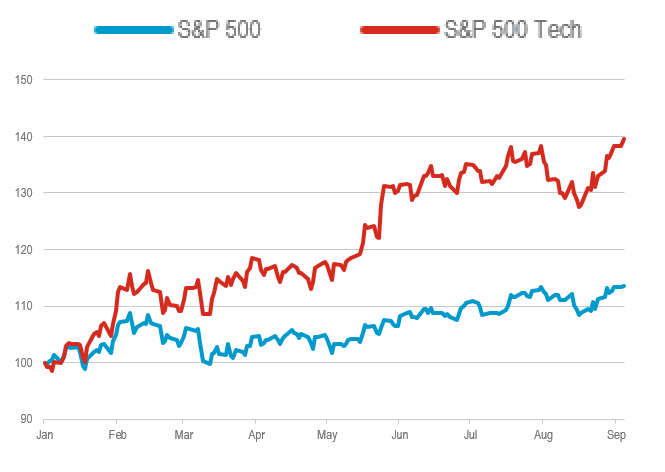

Figure 2: Rise of the machines

The technology sector has outperformed the broader S&P 500 Index substantially since the start of 2023:

Rebased to 100 on January 2023

Source: Refinitiv, Rathbones.

There will also be losers. Some jobs will be automated, and some companies will get disrupted in this new gold rush. We have already seen one company, the online education assistant Chegg, blame poor results on students using ChatGPT. There is a live debate about whether ChatGPT could dislodge Google Search’s near monopoly. The release of its own AI chatbot Bard is an early sign of Google’s ability to respond to this threat.

Identifying the losers isn’t straightforward. Unlike with previous technological disruptions, the winners may be today’s technology incumbents — they have the resources to develop the most sophisticated models while start-ups struggle to innovate as fast. We also think companies with large, proprietary data sets will also prosper, as they will have the training data to develop the most sophisticated AI models. Entrants lacking this data will struggle to compete. Adobe for instance can draw on its deep image library to train its generative AI tool.

Falling back down to earth

Markets are fickle, and we suspect many stocks that have seen their share prices surge in recent months will fall back down to earth as their earnings reports reveal a lack of boost to their revenue and profits from this technology. For instance, IT consultancy Accenture’s recent Q3 results showed that AI would have a negligible impact on revenues in the short term. They reckon only 5—10% of companies have the infrastructure, people or processes to start using generative AI.

Even if much of the hype is unjustified, many technology companies that may benefit in the long term are still trading at reasonable prices. For example, we think the large cloud service providers are likely to be able to drive the next leg of growth through selling AI services, as the backend of most AI applications will be hosted in the cloud. But that’s probably three to four years down the line. We also see other opportunities emerging for technology hardware companies like Arm, whose efficient semiconductors should be well suited to power hungry AI calculations in data centres. There are likely to be others.

While the potential for this technology is exciting, it’s uncertain how it will develop. At this stage we still think it makes sense to evaluate businesses according to their current earnings power rather than future visions of what generative AI might deliver.