Review of the week: Tax cuts or a conservative Budget?

UK Chancellor Jeremy Hunt will announce what is widely expected to be the last Budget of this government on Wednesday.

Article last updated 3 October 2025.

Quick take:

-

The Government is expected to deliver tax cuts this week in what looks to be its last Budget

-

Fiscal headroom of £20 billion has reportedly dropped to £13bn

-

‘Super Tuesday’ in America may lead to Republican candidate Nikki Haley finally conceding to Donald Trump

UK Chancellor Jeremy Hunt will announce what is widely expected to be the last Budget of this government on Wednesday.

With the Conservative Party lagging heavily in the polls, the Chancellor is trying to reinvigorate the government’s political fortunes and close the gap on the Labour Party. While it was recently reported that the UK fell into recession last year, it’s expected to be mild and fleeting – Bank of England (BoE) Governor Andrew Bailey has said it may in fact already be over. Hunt’s task is to boost the economy ahead of the election (which must be called before 28 January), and improve the national mood. If voters begin to feel better and more secure about the future, there’s a chance – however slim – that the Conservatives can pull off a comeback.

According to the Office for National Statistics’ Opinions and Lifestyle Survey, the joint largest concerns for people are the high cost of living and the parlous state of the NHS. Both were highlighted by 88% of people surveyed. The economy is next at 75%. A steady drip of leaks ahead of this week’s set piece suggests the government has set its sights on tax cuts to assuage voters’ concerns. And there is money for Hunt to play with.

Government tax receipts are higher than ever as frozen tax thresholds and lower tax-free allowances bite quicker and deeper. January tends to be a harvest month for the Treasury as self-assessed income tax payments are made, yet this year’s haul was slightly lower than government finances watchdog the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) had forecast back in November. Government borrowing was lower than expected as well, as lessened inflation drove down payments on inflation-linked government bonds. About a quarter of UK treasury bonds (gilts) are ‘index-linked’, so the drop in inflation has helped reduce the amount of cash the government needs to pay coupons and roll over maturing debts. The reduction in inflation has also driven down prevailing yields for government bonds, as investors anticipate interest rate cuts by the BoE. That means the Treasury can sell bonds at higher prices, getting a better rate on its loans and therefore securing more cash to use today and lessened interest payments over the term of the bonds.

For the government to deliver the tax cuts it hopes will turn around its election prospects, it must find the money from somewhere. It has handcuffed itself to fiscal rules that require government debt to fall, relative to the size of the economy, in five years’ time. While this is riddled with accounting sleights of hand that make predictions fanciful, it does mean the cash must come from existing areas of spending, rather than thin air.

A good slug of money ‘saved’ from better-than-expected economic conditions could be used this year, whether to cut taxes or increase funding for the NHS. Remember, even with this better outcome, the public debt is as big as the national economy and the government is spending over 5% more than it earns each year. At the beginning of the year, some economists estimated the Chancellor may have as much as £20 billion to play with. However, recent OBR forecasts have reportedly reduced this to £13bn. Spending all that money would ignore the chance of rough times ahead and the perhaps prudent decision to retain a rainy day fund.

It also ignores the large inflation-adjusted declines in budgets for public services over many years, i.e. it costs much more than in the past to offer the same standard of services. The steady increase in councils going bust or appealing for government help is a case in point. Some have been burned by questionable past decisions they made, yet most are overburdened by a statutory requirement to offer important services whose costs have ballooned, including emergency housing, rubbish collection and social care, while central government funding to help provide them has been greatly reduced. Not only that, but they are proscribed from raising council tax by central government in order to meet their fiscal needs. Independent policy thinktank the Institute for Fiscal Studies is concerned that this problem will only get worse in the coming years.

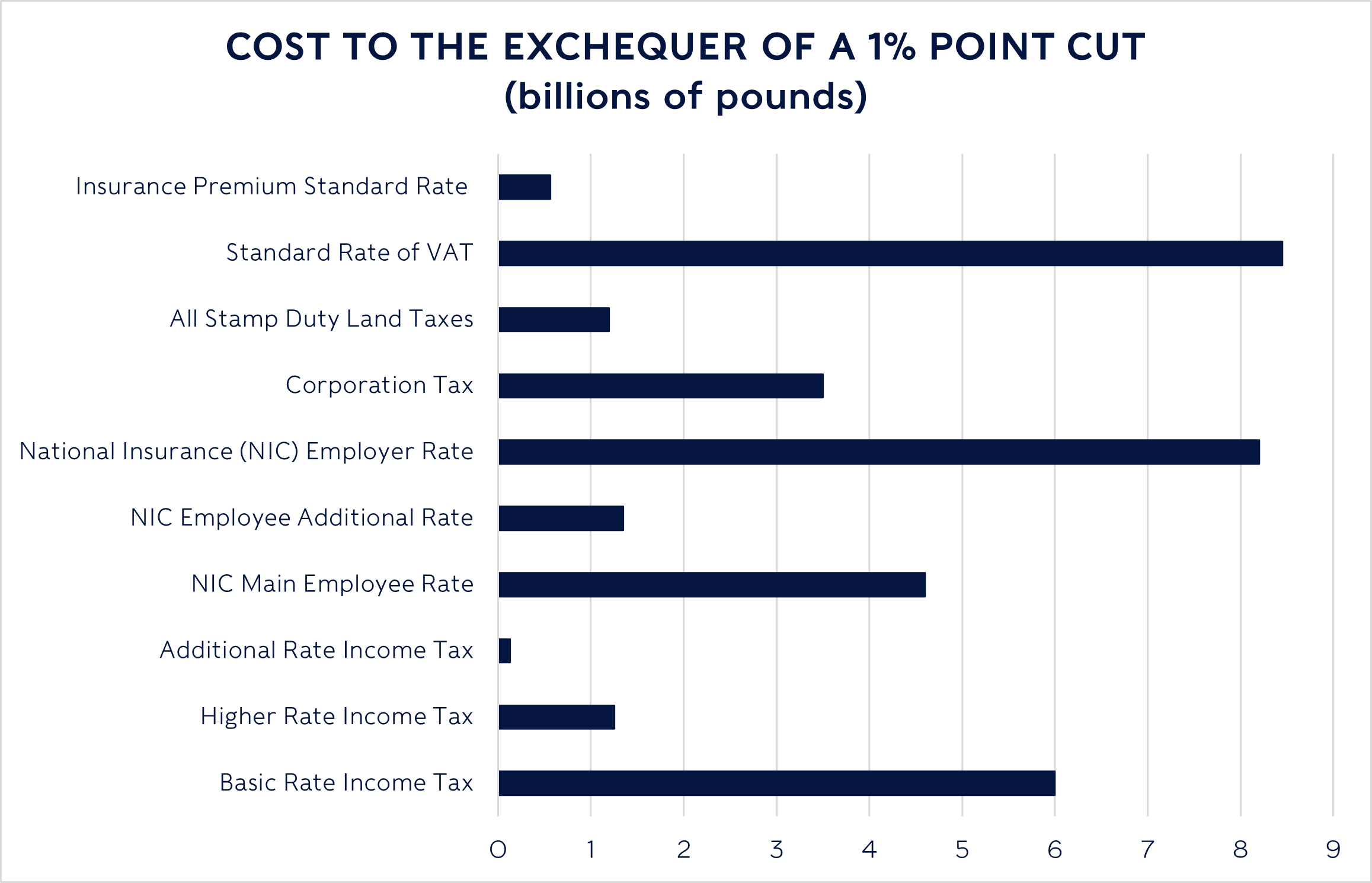

But to be around to deal with that problem you need to win the election this year. And no one ever won an election by thinking about tomorrow, so it seems highly likely that some form of tax cuts will be revealed this week. So what could Hunt do? The chart below shows the rough costs to the Treasury of changes to the main taxes. The rumour mill suggests the Chancellor wants to cut either Income Tax rates or National Insurance Contributions. The difference between the two is that NI is paid only by workers under the State Pension age (although, older self-employed workers do pay NI).

|

|

|

Source: HMRC, Rathbones; estimates for annual amounts for 2024/25 year only |

Look out for our thoughts on the Budget which will be published here by early Thursday.

| Index |

1 week |

3 months |

6 months |

1 year |

| FTSE All-Share |

-0.1% |

3.1% |

4.5% |

1.0% |

| FTSE 100 |

-0.2% |

2.7% |

4.3% |

1.0% |

| FTSE 250 |

1.0% |

5.8% |

6.0% |

0.9% |

| FTSE SmallCap |

0.2% |

5.1% |

5.5% |

1.6% |

| S&P 500 |

1.2% |

12.0% |

14.3% |

25.4% |

| Euro Stoxx |

0.7% |

8.3% |

11.0% |

9.9% |

| Topix |

2.4% |

11.9% |

13.1% |

19.7% |

| Shanghai SE |

0.9% |

-1.1% |

-2.8% |

-17.1% |

| FTSE Emerging |

-0.1% |

4.6% |

4.8% |

1.8% |

Source: EIKON, data sterling total return to 1 March

| These figures refer to past performance, which isn’t a reliable indicator of future returns. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and you may not get back what you originally invested. |

Coming up Trumps

It’s an important week for US politics as well. After weeks of back-to-back wins in the Republican Primaries for presidential contender Donald Trump, this week it’s crunch time.

This Tuesday is ‘Super Tuesday’, when a wave of state primaries are held all at once. These primaries can seem arcane and complicated, but they are actually pretty simple at their heart. They are a way to determine which candidate should represent political parties when they span 50 states. At each primary contest, candidates are vying for delegates. These delegates then head to the party conventions held later in the year to vote for the candidate they were pledged to.

Depending on each state’s rules and population, the delegates are pledged in proportion to the votes won or the winner takes them all. Once a candidate has secured a clear majority of delegates, they have essentially clinched the nomination and will be crowned officially at the convention. Sometimes, it’s too close to call and the convention can become an open war between candidates to secure the nomination. The most famous example of this was the Democratic Party Conference of Chicago in 1968, which degenerated into riots, police brutality and, eventually, a lost presidential campaign for Hubert Humphrey against Republican Richard Nixon.

This year’s Republican Party Conference is unlikely to go that way, as Donald Trump is currently leading his only remaining challenger, Nikki Haley, by a large margin. However, the simple fact that Haley has refused to quit the race has caused Trump some consternation – especially as he is facing innumerable civil and criminal court cases. This is no doubt why Haley has stubbornly remained in the running, despite only winning one state primary and losing her home state: if a particularly damaging case is lost by Trump, there may be a slim route to the nomination if he must pull out.

This Super Tuesday means about a third of all the state delegates are up for grabs, so it’s usually a clincher for the race. Voters in 15 states and one US territory total 874 Republican delegates at stake. If Haley loses convincingly once more, Super Tuesday may be the end of her campaign.

Primaries are being held by both parties, but the Democratic one is much less exciting and consequential. The incumbent, President Joe Biden, is essentially cemented in place as his party’s nominee.

If you have any questions or comments, or if there’s anything you would like to see covered here, please get in touch by emailing review@rathbones.com. We’d love to hear from you.